Principles of Insurance

Table of Contents

ToggleInsurance plays a pivotal role in providing financial security to individuals, businesses, and communities by mitigating risks. The development of the insurance industry in India has a rich and diverse history, with roots tracing back to ancient times and evolving significantly during the British colonial period and after independence. In insurance law, there are generally seven key principles of insurance that serve as the foundation for the functioning of the insurance contract and the obligations of both the insurer and the insured. These principles ensure fairness, transparency, and legal certainty in the insurance relationship. They are:

- The principle of Uberrimae Fidei (Utmost Good Faith).

- The principle of Insurable Interest.

- The principle of Indemnity.

- The principle of Subrogation.

- The principle of Contribution.

- The principle of Loss Minimization.

- The principle of proximate cause.

The principles of insurance are the foundational concepts that govern the functioning of the insurance industry. These principles ensure that the contract between the insurer and the insured is fair, transparent, and beneficial to both parties. Let’s explore the core principles of insurance in detail:

Principle of Utmost Good Faith (Uberrimae Fidei)

The Principle of Utmost Good Faith (Latin: uberrimae fidei) is one of the cornerstone doctrines of insurance law, ensuring that both parties, insured and insurer to act honestly and transparently throughout the life of the insurance contract. It obliges both parties to disclose all material facts that may influence the decision to enter into the contract. Any failure to comply with this duty can have serious legal consequences, including the voiding of the contract or a claim being denied. The principles of insurance are built on the foundation of trust, and utmost good faith is a prime example.

This article explores the principle of utmost good faith, its legal underpinnings, relevant case laws, and practical illustrations.

The Legal Basis for the Principle of Utmost Good Faith

The principle of utmost good faith is deeply rooted in both English and global insurance law, and is codified in several national legal frameworks. In common law jurisdictions, it is considered a basic duty that must be upheld by both parties to an insurance contract.

- English Law: The foundational law of utmost good faith in insurance contracts in England is found in the Marine Insurance Act 1906 (section 17). The Act prescribes that both the insurer and the insured must act with utmost good faith towards one another. Failure to do so can lead to the contract being voided, and any claims may be denied.

- Indian Law: Under Section 19 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, insurance contracts are considered contracts of uberrimae fidei, obligating both parties to disclose material facts. The Insurance Act, 1938 and subsequent judicial interpretations also emphasize the duty of disclosure.

- International Law: Many jurisdictions, particularly in civil law countries, have similar provisions either in their commercial or civil codes that impose the duty of good faith in the formation and performance of insurance contracts.

Key Features of Utmost Good Faith

- Duty of Disclosure: Both parties must disclose all material facts that could influence the decision of the other party. For the insured, this includes facts about the risk that the insurer may wish to assess. For the insurer, it includes providing clear and accurate terms of the contract.

- Material Facts: Material facts are those facts that would influence the decision of the insurer in determining whether to accept the risk, at what premium to charge, or on what terms to offer the insurance.

- Scope of Disclosure: The disclosure requirement is not limited to what is expressly asked by the insurer but includes any fact that is considered material and could influence the insurer’s decision.

- Consequences of Breach: Breach of the duty of utmost good faith—whether by non-disclosure, misrepresentation, or concealment—may result in the insurer being entitled to avoid the contract, deny claims, or even seek damages.

- Good Faith in Claims Process: The obligation of utmost good faith extends beyond the formation of the contract and continues through the performance of the contract, including the claims process. The insurer must process claims promptly and honestly.

Sections related to Utmost Good Faith

- Marine Insurance Act, 1906 (Section 17): This act requires both parties in a marine insurance contract to disclose all material facts and to act with utmost good faith.

- Insurance Act, 1938 (Section 45): This section deals with the disclosure of material facts and the consequences of non-disclosure in Indian law.

- Indian Contract Act, 1872 (Section 19): This section reiterates the principle of utmost good faith, particularly in contracts of insurance, where failure to disclose material facts leads to voiding of the contract.

Practical Illustrations

Example 1 – Car Insurance

An individual takes out car insurance without disclosing to the insurer that the car has been modified to include a high-performance engine. The insurer, relying on the disclosed information, may calculate premiums based on a standard vehicle. In the event of a claim, the insurer may void the contract or refuse payment, citing non-disclosure of material facts about the risk.

Example 2 – Health Insurance

A person applying for health insurance fails to disclose a history of a chronic illness, such as diabetes. Upon a claim for medical treatment, the insurer discovers the non-disclosure and may deny the claim or cancel the policy, relying on the principle of utmost good faith.

Case Study: Non-Disclosure and Its Consequences

Case Study 1: A Life Insurance Policy Application

Background: An individual, Mr. X, applies for life insurance, claiming he is in good health. However, Mr. X is suffering from a condition, such as hypertension, which he fails to disclose in the application form. After a few years, Mr. X dies due to complications related to hypertension. When the insurer investigates the claim, it is discovered that Mr. X had not disclosed his medical condition.

Outcome: The insurer may invoke the principle of utmost good faith and void the contract, stating that Mr. X’s failure to disclose a material fact influenced the insurer’s decision to provide the policy. As the non-disclosure was found to be material and affected the insurer’s risk assessment, the insurer can deny the death benefit claim.

Key Points and Features

- Disclosure is a Continuous Duty: The duty to disclose material facts is continuous, meaning that it does not end at the point of entering into the contract but continues throughout the life of the contract.

- The Insured’s Obligation: The primary duty of disclosure falls on the insured, as they are the party with the most knowledge of the facts relevant to the risk being insured.

- Breach and Consequences: A breach of the duty of utmost good faith can result in voiding the contract, refusal of claims, and in some cases, the insurer may also pursue damages for any fraudulent misrepresentation.

- Standard of Disclosure: The standard of disclosure is strict, and non-disclosure is not excused simply because the insured believed that the fact was not important or was known to the insurer.

The principle of utmost good faith serves as a protective mechanism in insurance law, ensuring transparency, fairness, and the mitigation of moral hazard. By requiring both insurers and the insured to disclose material facts and act with honesty, it upholds the integrity of the insurance contract. The failure to abide by this principle, as demonstrated in various case laws, can lead to significant legal and financial consequences for both parties. Thus, the application of utmost good faith is not just a formal requirement but a crucial part of the trust that underpins insurance relationships.

Read about in detail: Principle of Utmost Good Faith in Insurance Law

Principle of Insurable Interest

Insurable interest refers to the financial or economic stake that an individual or entity must have in the subject matter of the insurance policy. Simply put, the insured must stand to lose something of value if an insured event occurs. In other words, the policyholder must be directly affected by the loss to the property, life, or asset being insured. The existence of this interest is a legal requirement for the validity of most insurance contracts.

Without insurable interest, an individual could take out an insurance policy on someone else’s property or life, which could lead to unethical and fraudulent behavior, such as intentionally causing a loss to benefit from the policy. Among the fundamental principles of insurance, insurable interest ensures that the policyholder has a legitimate stake in the insured object or person. The principles of insurance aim to prevent profit-making from claims.

The Importance of Insurable Interest

- Prevents Gambling on Losses: The principle of insurable interest prevents individuals from taking out insurance policies on things or people in which they have no real financial stake. This would otherwise create a situation where people could “gamble” on events causing loss. Insurable interest ensures that insurance remains a tool for risk management rather than speculation.

- Reduces Fraud and Moral Hazard: If someone is financially unaffected by the destruction of a property or the death of a person, they might have a motive to cause that loss. For example, someone who does not own a building could intentionally set it on fire, knowing they stand to gain the insurance payout. By requiring insurable interest, insurance companies reduce the risk of fraud and moral hazard.

- Clarifies the Right to Claim: Insurable interest establishes a clear right for the policyholder to make a claim. Without this, it would be impossible to determine who is entitled to the benefits of an insurance policy in case of a loss. It ensures that only those with a legitimate stake in the property or life covered are entitled to compensation.

Insurable Interest in Life Insurance

In life insurance, the principle of insurable interest plays an essential role in determining who can take out a policy on someone’s life. The policyholder must have a financial interest in the continued life of the insured person.

Key Considerations in Life Insurance:

- Family Members: A person has an insurable interest in the life of a spouse, children, or other immediate family members, because the death of a family member would likely cause emotional, financial, and practical hardship.

- Business Partners: Business partners can insure each other’s lives to cover the financial losses their business would incur in case of death. This is especially common in partnership agreements to safeguard the continuity of the business.

- Creditors: Creditors may take out life insurance policies on the lives of debtors to ensure that the outstanding debts can be repaid in case of the debtor’s death. However, the amount of insurance cannot exceed the value of the debt.

Example: If a husband insures his wife’s life, he has an insurable interest in her life because her death would likely lead to financial and personal hardship. However, a person cannot take out a life insurance policy on a random individual, such as a neighbour, without a legitimate reason, as they do not have a financial stake in the person’s life.

Insurable Interest in Non-Life Insurance

In non-life insurance, such as property, health, and vehicle insurance, the principle of insurable interest ensures that the policyholder has a tangible financial stake in the insured property or asset.

Key Considerations in Non-Life Insurance:

- Property Insurance: A person must have ownership or a legal interest in the property being insured. For example, a homeowner can insure their house, but a tenant can only insure the contents of the house, not the building itself, because they do not own the property.

- Motor Insurance: In motor insurance, the policyholder must have a financial interest in the vehicle. A person can insure their own car, but they cannot insure someone else’s car without the owner’s permission, as they have no financial stake in the vehicle.

- Health Insurance: In health insurance, the principle of insurable interest is also essential. A person can take out a policy to cover their own health, and in some cases, they can insure the health of family members (spouse, children, etc.).

Example: If a person owns a car and insures it against theft or damage, they have insurable interest in that vehicle because they stand to lose financially if the car is damaged or stolen. A person who does not own the car, on the other hand, has no insurable interest in the vehicle and therefore cannot legally insure it.

Legal Requirements for Insurable Interest

The existence of insurable interest is not just a moral or ethical requirement; it is also a legal one. Most countries, including India, have laws that mandate the presence of insurable interest in an insurance contract.

For Life Insurance:

- The insurable interest must exist at the time of purchasing the policy, but it is not required to be present at the time of the insured event (such as death).

- The policyholder’s relationship with the insured person must be one where the death of the insured would result in a financial loss to the policyholder.

For Non-Life Insurance:

- Insurable interest must exist at both the time of taking out the policy and at the time of the loss. For example, a person must own the property at the time of insuring it and still own it when the loss occurs.

Legal Precedents in India: Under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, the requirement of insurable interest is explicitly mentioned for various insurance contracts. Section 10 of the Act requires that the contract must involve a lawful consideration, and in the case of insurance, this consideration is the insurable interest of the policyholder.

The Duration of Insurable Interest

In life insurance, the requirement for insurable interest exists at the inception of the policy. In non-life insurance, insurable interest must exist at the time of the claim. For instance, if a person sells their car and then tries to claim insurance for damage to it, they would not be entitled to a payout because they no longer have an insurable interest in the vehicle.

Principle of Indemnity

The principle of indemnity is fundamental in most non-life insurance contracts and ensures that the insured is compensated for their financial loss but not overcompensated to the extent that they make a profit from the insurance claim. Simply put, indemnity means compensation for an actual financial loss, with the goal of putting the insured in the same financial position as they were prior to the loss, without allowing them to gain or lose from the transaction. The principles of insurance aim to prevent profit-making from claims.

Definition and Concept of Indemnity

The principle of indemnity may be encapsulated by the maxim: “Nemo debet locupletari ex alieno damno” (No one should be enriched at another’s expense). This principle dictates that an insured party should not suffer a financial loss as a result of an insured event, yet simultaneously, they should not be permitted to gain from the insurance contract. The objective is to ensure that the insured is merely restored to their original financial position, without any element of profit or unjust enrichment.

This serves as a safeguard against the potential abuse of the insurance mechanism, particularly to prevent moral hazard — the situation where the insured may be incentivized to act recklessly or negligently, knowing that they will be compensated for any resulting loss. Under the principle of indemnity, the insurer’s liability is strictly confined to compensating the insured for the actual loss incurred, based on the “value in use” or the actual value of the property, liability, or damage sustained, rather than a speculative or hypothetical value.

The principle of indemnity ensures that insurance serves its true purpose: to protect the insured from financial loss, while preventing them from making a profit from the insurance claim. This principle is particularly relevant in non-life insurance contracts, such as property and liability insurance, where the insurer’s liability is limited to the actual loss or damage suffered by the insured.

Though exceptions exist in cases like life insurance or valued policies, the general rule is clear: the insured should be compensated for their loss, but not beyond it. Understanding the principle of indemnity is essential for both insurers and policyholders to ensure that insurance contracts are fair, transparent, and effective in managing risk. Thus, indemnity ensures fairness and prevents unjust enrichment, aligning with the legal maxim “Restitutio in integrum” (restoration to the original position).

For example, if a motor vehicle is insured for ₹5,00,000 but the market value at the time of loss is ₹3,50,000, the insurer is obligated to compensate the insured for the actual loss sustained — ₹3,50,000 — rather than the higher insured amount. The insured cannot claim a sum exceeding the actual value of the loss, thus preventing excessive compensation or profit from insurance.

Key Elements of the Principle of Indemnity:

- Actual Loss: The payout is limited to the actual financial loss incurred.

- No Profit: The insured cannot profit from the insurance claim.

- Restoration to Original Position: The aim is to restore the insured’s financial position before the loss.

Application of the Principle of Indemnity

– Indemnity in Property Insurance

Property insurance, which covers assets like homes, vehicles, and businesses, operates largely on the principle of indemnity. This means that if an insured property is damaged, the insurer will compensate the insured for the repair or replacement costs, but only up to the value of the property at the time of loss. The amount of compensation will not exceed the market value or the cost of repairing the property, whichever is lower.

For example, suppose a person insures their house for ₹10,00,000 but the market value of the property is only ₹6,00,000. If a fire occurs and damages the house to the extent of ₹4,00,000, the insurer will only pay the actual loss incurred, i.e., ₹4,00,000. In no case will the insurer pay more than the actual loss or the value of the insured property.

Example: If an insured car worth ₹4,00,000 gets into an accident and sustains damages amounting to ₹2,00,000, the insurer will pay ₹2,00,000 as compensation, even if the sum insured was ₹5,00,000. This ensures that the insured is not overcompensated.

– Indemnity in Liability Insurance

Liability insurance covers the policyholder for legal costs and damages in the event of a claim filed by a third party. The principle of indemnity here ensures that the insurer compensates the policyholder for the actual legal costs or liabilities incurred, and the insured will not be entitled to more than the amount of the actual financial loss.

For example, in professional indemnity insurance, a lawyer or doctor may be covered for the legal costs if they are sued for malpractice. If the third-party claim results in a ₹5,00,000 judgment against the insured, the insurer will indemnify the policyholder up to that amount, not exceeding the actual judgment.

Example: A company holds a general liability insurance policy for ₹10,00,000. If the company is found liable for ₹7,00,000 in damages to a third party due to negligence, the insurer will pay ₹7,00,000. Even though the company is insured for a higher amount (₹10,00,000), the payout is limited to the actual loss of ₹7,00,000.

-Indemnity in Life Insurance

While life insurance is not strictly governed by the indemnity principle (because it is not concerned with indemnifying against financial loss in the same sense as property or liability insurance), it is relevant to note that life insurance operates on the basis of an agreed sum, often referred to as the “sum assured” or “death benefit.” In this case, the principle of indemnity does not apply in the traditional sense, as life insurance is meant to provide financial security to the beneficiaries of the policyholder, irrespective of the actual financial loss.

Key Difference: In life insurance, the payout is a fixed amount, agreed upon at the inception of the policy, which is paid out upon the death of the policyholder. The payout does not depend on the financial loss suffered by the beneficiary due to the death.

Example: If an individual purchases a life insurance policy with a sum assured of ₹10,00,000, and they pass away, their beneficiaries receive the full ₹10,00,000, regardless of the financial loss the family might have incurred.

Legal Provisions and Case Laws

The principle of indemnity is supported by various legal provisions, especially under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and the Insurance Act, 1938. These legal frameworks define the scope of insurance contracts, the obligations of insurers, and the insured’s rights.

- Indian Contract Act, 1872 – Section 124

Section 124 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, defines a contract of insurance as a contract in which one party agrees to compensate the other in the event of a specified loss, as a result of certain risks. This section lays the groundwork for the indemnity principle by establishing the insurer’s duty to indemnify the insured. - Insurance Act, 1938 – Section 64VB

Section 64VB of the Insurance Act, 1938 requires that the premium be paid before the commencement of the insurance cover. While this section does not explicitly address indemnity, it ensures that insurance contracts are legally binding only when the premium is paid, enabling the application of the indemnity principle.

Case Laws Illustrating the Principle of Indemnity

Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Haji Sayeed & Ors.

In this case, the insured’s property was damaged in a fire. The Supreme Court ruled that under a fire insurance policy, the insurer was only liable to pay the actual loss incurred by the insured. The payout could not exceed the market value of the property at the time of loss, thus reinforcing the principle of indemnity.

Bajaj Allianz General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Bank of India (2009)

In this case, the bank had insured the cash-in-transit, and the loss occurred due to a robbery. The Supreme Court emphasized that the insurer was liable only to the extent of the actual loss incurred and could not be held liable for any amount exceeding the value of the stolen cash.

Exceptions to the Principle of Indemnity

While the principle of indemnity is fundamental, there are several key exceptions to its application:

- Life Insurance

In life insurance contracts, the principle of indemnity does not apply. Life insurance is based on the concept of providing financial protection to the beneficiaries of the insured. The sum assured under a life insurance policy is predetermined and does not depend on the actual financial loss suffered by the beneficiary. - Valued Policies

In some situations, such as in certain marine insurance contracts, a “valued policy” may be issued. This type of policy specifies an agreed amount that will be paid in the event of a loss, irrespective of the actual value of the property. For example, a painting valued at ₹1,00,000 may be insured for that amount under a valued policy, even though its actual market value may fluctuate. - Agreed Amount in Health and Accident Insurance

In accident or health insurance, the insurer may agree to pay a fixed sum for a specific injury or health condition, regardless of the actual medical expenses incurred. This differs from indemnity policies, where compensation is based on actual costs.

Principle of Subrogation

The principle of subrogation occupies a pivotal place in Indian insurance law. It refers to the right of an insurer, upon indemnifying the insured for a loss, to step into the shoes of the insured and pursue any third party responsible for the damage. This doctrine ensures that the financial burden of the loss ultimately falls upon the party legally accountable for it, rather than the insurer, thereby mitigating the insurer’s financial exposure and preventing unjust enrichment of the insured. The principle is not merely a contractual stipulation but an essential tenet of equity and justice in insurance law.

Subrogation, one of the critical principles of insurance, allows insurers to recover losses from a third party responsible for causing the damage, ensuring fairness in the claims process.

This section provides an in-depth examination of the principle of subrogation in Indian insurance law, including its legal basis, statutory framework, pertinent case laws, key features, and the practical implications of its application. The discussion further explores relevant legal maxims and their relationship to subrogation.

Legal Basis and Statutory Framework

The principle of subrogation in Indian insurance law is not expressly codified in a single statutory provision but is rather embedded within the general principles of insurance contracts and civil law. The right to subrogate arises as an implication of the insurer’s duty to indemnify the insured, subject to the terms of the policy.

1. Indian Contract Act, 1872

Although the Indian Contract Act, 1872 does not specifically mention subrogation, Section 79 can be regarded as indirectly acknowledging the principle. Section 79 outlines the concept of “rights of a party to stand in the place of another for the purpose of recovering money,” which is analogous to the concept of subrogation. This provision supports the idea that, upon indemnification, the insurer assumes the rights of the insured to recover the amount from a third party responsible for the loss.

2. The Insurance Act, 1938

The Insurance Act, 1938 is the principal statute governing the insurance industry in India. While it does not explicitly deal with the principle of subrogation, it establishes the legal framework within which insurance contracts operate. The Act stipulates the requirements for valid contracts, the duties of insurers and insured parties, and the handling of claims. It is in this contractual context that subrogation rights are implied, particularly where the insurer is obligated to indemnify the insured and subsequently seeks to recover the compensation from a third-party tortfeasor.

3. Marine Insurance Act, 1963

In the domain of marine insurance, subrogation is specifically addressed by Section 79 of the Marine Insurance Act, 1963, which sets out the insurer’s right to recover from third parties responsible for the loss after indemnifying the insured. The section enunciates the insurer’s entitlement to pursue a claim against a third-party tortfeasor following the settlement of a marine insurance claim, making it one of the clearest statutory articulations of the subrogation principle.

4. Customary Law of Insurance

The principle of subrogation is further supported by the well-established customs in the insurance industry, especially in cases involving property, fire, and vehicle insurance. Insurers routinely exercise the right of subrogation when they compensate the insured for a loss caused by the negligence or wrongful act of a third party.

Concept and Mechanics of Subrogation

Subrogation is a legal fiction that allows an insurer to assume the rights of the insured against third parties after indemnifying the insured for a loss. It is based on the maxim “ex dolo malo non oritur actio”, meaning that no legal right arises from a wrongful act, and therefore, the insurer is entitled to pursue the third party to recover the amount paid to the insured.

The following key points highlight the mechanics of subrogation:

- Insurer’s Right to Recovery

Once the insurer has compensated the insured for a loss, the insurer becomes entitled to recover the indemnified amount from the third party responsible for the loss. This right is derived from the insurer standing in the shoes of the insured. The insurer’s pursuit of the third party is not a gratuitous act but a means to mitigate the financial exposure caused by the indemnity. - Prevention of Double Recovery

The principle of subrogation ensures that the insured does not receive double compensation for the same loss—once from the insurer and again from the responsible third party. The insurer, by exercising its right of subrogation, recoups the amount paid to the insured, thereby ensuring that the insured does not profit from the loss beyond what is necessary to make them whole. - Substitution of Rights

Upon paying the claim, the insurer effectively assumes the insured’s right to recover the compensation from the third party. The insured’s original claim against the third party is thus “transferred” to the insurer. The insurer may pursue legal remedies available to the insured, including filing a suit for damages, against the third party. - No Effect on Insured’s Right to Recover

Subrogation does not affect the insured’s right to pursue their own recovery from the third party if the insurer has not compensated them. However, once indemnification has occurred, the insurer becomes the party entitled to pursue the third party for the loss.

Legal Maxims Related to Subrogation

- “Injuria sine damno” – Injury without damage: This maxim underscores the concept that the right to recover arises only when a loss or injury is sustained. In the context of subrogation, the insurer is entitled to pursue the responsible third party for the recovery of the amount paid to indemnify the insured for the injury (the loss) suffered.

- “Damnum sine injuria” – Damage without injury: This principle reinforces that a person may not recover damages for loss unless there is an actionable injury or wrongful conduct. In cases where a third party’s actions have led to the damage, subrogation allows the insurer to recover from the third party on behalf of the insured, as there is an actionable injury (the loss caused by the third party’s negligence).

- “Ex turpi causa non oritur actio” – No action arises from an immoral cause: This maxim holds that a legal right cannot arise from an unlawful or immoral act. In subrogation, the insurer may not recover from a third party involved in an illegal act if the recovery would amount to unjust enrichment. For example, if the insured and the third party had colluded in the commission of a fraud, the insurer would not be entitled to subrogate and recover the amount paid to the insured.

- “Nemo dat quod non habet” – No one can give what they do not have: This maxim applies in subrogation, as the insurer’s rights to recover from a third party are derivative of the insured’s original rights. The insurer can only recover from the third party to the extent that the insured would have been entitled to recover. Therefore, the insurer’s rights are limited to the amount actually paid to the insured.

Key Features of Subrogation in Indian Insurance Law

- Insurer’s Right to Step into the Insured’s Shoes

Once an insurer indemnifies the insured for a loss, the insurer acquires the legal right to pursue any third party whose actions were responsible for the loss. The insurer steps into the place of the insured and inherits the insured’s right of action against the third-party tortfeasor. - Duty of Cooperation of the Insured

The insured is obligated to assist the insurer in exercising its subrogation rights. This includes providing information, documents, and any other assistance necessary for the insurer to pursue the responsible third party. Additionally, the insured must refrain from settling or compromising with the third party without the insurer’s consent, as doing so may prejudice the insurer’s right to recover. - Third-Party Liability

Subrogation typically arises where a third party, through negligence or wrongful conduct, is responsible for causing the loss. In such cases, after indemnifying the insured, the insurer may initiate legal proceedings against the third party to recover the amounts paid out under the policy. - No Double Recovery

The insured is prohibited from receiving compensation twice for the same loss, once from the insurer and once from the third party. Subrogation ensures that the financial loss is only compensated once. If the insured has already received compensation from the insurer, any recovery from the third party belongs to the insurer, up to the amount indemnified. - Limitations on Subrogation

The right of subrogation is not unlimited. The insurer’s rights are governed by the terms and conditions of the insurance policy. If the insured acts in bad faith—for example, by settling with the third party without informing the insurer or by taking actions that affect the insurer’s ability to recover—the insurer’s right to subrogation may be limited or extinguished.

Case Laws and Judicial Precedents

Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Narinder Singh [2004]

This case reinforced the insurer’s right of subrogation in motor vehicle insurance. The Supreme Court held that after indemnifying the insured, the insurer is entitled to recover

the compensation from the third party who caused the accident. The insurer may pursue legal action against the responsible party to recover the amount paid out under the policy.

United India Insurance Co. Ltd. v. R. Krishnan [2013]

In this case, the Supreme Court reiterated that the insurer’s right to subrogate arises only after indemnifying the insured, and the insurer’s right is enforceable against any third party responsible for the loss.

Practical Illustration

- Motor Vehicle Insurance

Mr. A’s vehicle is involved in an accident caused by the negligent driving of Mr. B. Mr. A files a claim with XYZ Insurance Company, which indemnifies him for the damage to his vehicle. Under the principle of subrogation, XYZ Insurance Company then acquires the right to recover the indemnified amount from Mr. B, the responsible third party. - Property Insurance

Mrs. X owns a house that is insured against fire damage. The fire is caused by faulty electrical wiring installed by a third party, Mr. Y. The insurer compensates Mrs. X for the repairs. Under subrogation, the insurer can then recover the amount from Mr. Y, who was responsible for the damage.

The principle of subrogation is a fundamental aspect of Indian insurance law that ensures fairness and prevents unjust enrichment. By allowing insurers to recover compensation from third parties after indemnifying the insured, it helps to distribute the financial burden of the loss to the responsible party. The principle not only ensures that the insurer can mitigate its financial exposure but also preserves the integrity of the insurance contract by preventing double recovery by the insured. Understanding the mechanics and scope of subrogation is essential for both insurers and insured parties to navigate claims efficiently and in compliance with the law.

Principle of Contribution

The principle of contribution in insurance law arises when a policyholder has multiple insurance policies covering the same risk. This principle ensures that when a loss occurs, the burden of indemnification is shared proportionally among all the insurers. It aims to prevent the insured from recovering more than the actual loss, thereby preserving the fundamental doctrine of indemnity, and prevents unjust enrichment. The principles of insurance include contribution, which applies when multiple policies cover the same risk.

In essence, if an insured has more than one insurance policy covering the same risk, each insurer’s liability is proportionate to the sum insured under its respective policy. The principle of contribution ensures that the insured does not profit by receiving more compensation than the actual loss sustained.

Concept of Contribution

The principle of contribution can be succinctly expressed by the maxim “Nemo debet bis vexari pro una et eadem causa” (No man should be twice vexed for the same cause). In insurance, this means that if a person is insured under multiple policies for the same risk, the insurers are collectively liable to compensate the insured for the loss, but each insurer’s liability will be in proportion to the coverage it provides.

When more than one insurance policy covers a loss, and the insured claims the full amount of the loss from each insurer, the principle of contribution prevents the insured from collecting more than their actual loss. Instead, the insurers will share the responsibility for the indemnity according to a set of rules determined by the nature of their policies, such as the ratio of the sum insured.

Legal Basis of the Principle of Contribution

The principle of contribution is primarily governed by the provisions of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and specific provisions under the Insurance Act, 1938. In India, contribution arises only when the following conditions are met:

- Multiple Insurance Policies: The same risk must be insured under two or more policies. The insured must have multiple insurance policies covering the same subject matter.

- Same Interest: The policies must be on the same interest, meaning they must relate to the same insured property or liability.

- Indemnity Insurance: The principle of contribution applies only to policies of indemnity (not life insurance or policies with fixed sums) where the loss can be quantified in terms of financial value.

Section 68 of the Insurance Act, 1938 deals with contribution, specifically with regard to co-insurance and the limits of indemnity. Under this section, an insurer is required to contribute to the loss when there are multiple policies covering the same risk.

The Principle in Action: Proportional Liability

Under the principle of contribution, each insurer contributes to the indemnity in proportion to the amount they insure the risk for, relative to the total amount of insurance coverage. This proportionate contribution is generally calculated by the following formula:

This ensures that no insurer is overburdened and that the insured does not benefit disproportionately from the multiple policies.

Example 1: Contribution in Property Insurance

Assume a property is insured for ₹5,00,000 under Policy A, and ₹3,00,000 under Policy B. If a fire causes a loss of ₹4,00,000, the insurers will contribute in proportion to their respective sums insured.

Thus, the insured would receive ₹2,50,000 from Policy A and ₹1,50,000 from Policy B, totaling the actual loss of ₹4,00,000.

Example 2: Contribution in Marine Insurance

In marine insurance, multiple policies often cover a vessel or cargo. If a ship carrying goods is damaged in a storm, and there are two insurance policies-

one for ₹10,00,000 and another for ₹5,00,000, the principle of contribution ensures that both insurers pay proportionately.

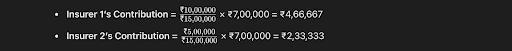

If the damage to the cargo amounts to ₹7,00,000, the insurers will contribute as follows:

Exceptions to the Principle of Contribution

While the principle of contribution applies in the vast majority of cases, there are certain exceptions and scenarios where it may not apply or is limited:

Life Insurance Policies: Contribution does not apply to life insurance policies. Life insurance contracts are governed by the principle of “utmost good faith” (uberrimae

fidei), and each insurer’s liability is determined by the specific terms of the policy. In case of multiple life insurance policies, the beneficiaries are entitled to claim the full sum assured from each insurer, irrespective of other policies.

- Policy with No Contribution Clause:

If one of the policies contains a “non-contribution” clause, it may specify that the insurer is not liable to contribute to a claim if the insured holds another policy covering the same risk. In such cases, the insurer with the non-contribution clause may not be required to pay, even if other policies are in place. - Different Types of Insurance:

Contribution is applicable only where the policies cover the same type of risk or interest. If one policy covers the property and another covers liability, the principle of contribution does not apply. - First Loss Policies:

A first-loss policy may not participate in contribution. Such policies are designed to provide coverage only for the initial loss up to a certain limit, and beyond that limit, other policies with broader coverage may step in.

Relevant Case Laws

The principle of contribution has been discussed and clarified in several Indian cases, where the courts have dealt with disputes arising from multiple insurance policies covering the same risk.

United India Insurance Co. Ltd. v. M/s. Pushpalaya Printers (2004)

In this case, the Supreme Court held that where the insured has multiple policies for the same risk, the insurers are bound to contribute towards the loss in proportion to the sum insured by each policy. The court emphasized that the insured can claim the full amount of loss, but each insurer’s liability is restricted to its proportionate share.

New India Assurance Co. Ltd. v. Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd.

In this case, the issue was whether two insurers, who had insured the same property under different policies, were bound to contribute proportionately towards the settlement of a claim. The court ruled that the principle of contribution would apply, with each insurer’s liability being limited to its proportion of the total sum insured.

Legal Maxims Relevant to Contribution

Several legal maxims help elucidate the operation of the principle of contribution:

- “Nemo debet bis vexari pro una et eadem causa” (No one should be twice vexed for the same cause): This maxim underlines the idea that a person should not be made to bear the same burden twice, and in the context of insurance, it ensures that no more than the actual loss is recovered by the insured.

- “In pari delicto potior est conditio defendentis” (In cases of equal fault, the position of the defendant is preferable): This maxim finds application in cases where insurers have contributed equally, establishing that insurers share equally in the liability.

- “Caveat emptor” (Let the buyer beware): While this maxim is generally used in contract law, it can be applicable in insurance, urging policyholders to be mindful of the terms of their policies, including contribution clauses, which could affect their rights in case of multiple policies.

The principle of contribution ensures fairness and consistency in the insurance industry by preventing unjust enrichment and guaranteeing that the insured is indemnified only for the actual loss sustained. It operates on the fundamental principle that no party should be paid more than the loss it has incurred (“Restitutio in integrum”).

While the principle is widely applicable, it is important for policyholders to understand the conditions under which contribution applies, the calculation method, and potential exceptions such as life insurance policies or those with specific clauses.

Ultimately, contribution serves as a mechanism to uphold the integrity of insurance contracts, ensuring that the process remains just, equitable, and aligned with the principles of indemnity and fairness. The Indian courts have consistently upheld the application of this principle in multiple rulings

Principle of Loss Minimization

The principle of loss minimization is an essential doctrine in Indian insurance law that underscores the insured’s duty to take reasonable steps to prevent or reduce the extent of damage following an incident that could give rise to an insurance claim. This principle is grounded in the concept of fairness and reasonableness, ensuring that insurers are not burdened with claims arising from an insured’s negligence in mitigating the loss. It is a reciprocal duty: while the insurer is obligated to indemnify the insured for the losses suffered, the insured must act prudently and promptly to limit further damage. Aligned with the principles of insurance, this principle emphasizes the insured’s responsibility to minimize losses.

In this section, we examine the principle of loss minimization in Indian insurance law, its statutory and contractual foundations, key features, legal maxims, relevant case law, and practical illustrations.

Legal Basis and Statutory Framework

The principle of loss minimization is primarily governed by the terms and conditions set forth in insurance contracts and is a common law concept. While Indian statutory law does not contain an explicit provision regarding loss minimization, it is an implied term in most insurance policies. Its application can be found in the following legal frameworks:

1. Indian Contract Act, 1872

The Indian Contract Act, 1872 lays the foundation for most contractual obligations, including insurance contracts. Section 73 of the Indian Contract Act deals with the concept of “compensation for loss or damage caused by a breach of contract,” which indirectly supports the principle of loss minimization. It imposes an obligation on the parties to mitigate the loss, which in the context of insurance law translates to the insured’s duty to take reasonable measures to minimize damage after the loss occurs.

2. The Insurance Act, 1938

The Insurance Act, 1938 governs the overall framework of the insurance industry in India. Although it does not explicitly address the principle of loss minimization, it outlines the duties of the insured and the insurer under insurance contracts. Section 64-VB of the Act requires that insurance policies be written in clear terms, and insurers have the right to include clauses that mandate the insured’s cooperation in minimizing loss. Any failure to comply with such clauses could affect the insured’s entitlement to compensation.

3. The Marine Insurance Act, 1963

In marine insurance, the principle of loss minimization is explicitly recognized. The Marine Insurance Act, 1963 places a duty on the insured to take all reasonable steps to prevent further loss or damage after the insured peril occurs. Section 78 of the Act specifically requires the insured to “use all reasonable means to avoid or minimize a loss” once the loss has been sustained.

4. Policy Conditions and Terms

The specific terms governing the principle of loss minimization are generally incorporated into the terms of the insurance policy. Clauses related to “Duty of Care,” “Duty to Mitigate Loss,” or “Reasonable Steps” are commonly included in policies. These clauses specify that the insured must act to prevent further damage after the loss has occurred, and failure to do so could result in a reduction or denial of the claim.

Concept and Mechanics of Loss Minimization

The principle of loss minimization arises from the broader concept of mitigation of damages in legal theory. It requires the insured to act reasonably in reducing the scope or quantum of loss after the occurrence of an insured event.

Key Aspects of Loss Minimization

- Duty to Act Promptly

The insured is obligated to take immediate steps to reduce or prevent further loss. This duty is particularly relevant in cases of fire, flooding, or theft, where delays in action can exacerbate the damage. - Reasonableness of Measures

The steps taken by the insured must be reasonable, considering the nature of the loss and the circumstances. This means that while the insured need not take extraordinary measures, they are expected to take ordinary precautions and actions that a prudent person would undertake in similar circumstances. - Incurred Costs of Mitigation

In certain cases, the costs incurred by the insured in mitigating the loss (e.g., repair expenses or temporary measures to prevent further damage) may be reimbursable under the policy, provided that the steps taken were reasonable and aligned with the duty to minimize loss. - Consequences of Failure to Minimize Loss

If the insured fails to minimize the loss, the insurer may reduce the amount payable under the claim or, in extreme cases, refuse to indemnify the insured altogether. The failure to act in a timely or reasonable manner could be seen as a violation of the insurance contract.

Legal Maxims Related to Loss Minimization

Several legal maxims are relevant to the principle of loss minimization in insurance law:

- “Actus reus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea” – The act is not wrongful unless done with a guilty mind: In the context of loss minimization, this maxim highlights that a failure to act does not automatically result in liability. However, the insured’s failure to minimize loss must be deliberate or grossly negligent to affect their claim.

- “Volenti non fit injuria” – To a willing person, no injury is done: This maxim underscores the idea that an insured party cannot claim for damage that results from their own voluntary failure to take reasonable steps to prevent further harm.

- “Nemo dat quod non habet” – No one can give what they do not have: This maxim is relevant in cases where the insured fails to mitigate loss, as the insurer may refuse to provide compensation for losses that the insured could have reasonably avoided.

- “Damnum sine injuria” – Damage without injury: This principle suggests that the mere fact of damage does not necessarily result in a compensable claim. In insurance law, if the insured fails to mitigate loss, the insurer may argue that the loss could have been avoided, thus no compensable injury has occurred.

Key Features of Loss Minimization in Indian Insurance Law

- Duty of the Insured to Prevent Further Damage

The insured must take all reasonable precautions to prevent further damage after the insured peril occurs. This includes actions such as notifying authorities, securing the premises, or employing emergency measures to control the damage. - Insurer’s Right to Reject Claims for Failure to Mitigate Loss

If the insured fails to minimize the loss in accordance with the policy’s conditions, the insurer has the right to reduce the payout or reject the claim outright. This serves as an incentive for the insured to act promptly and responsibly in mitigating potential damage. - Scope of the Duty to Minimize Loss

The extent of the insured’s obligation to minimize loss is typically defined in the insurance policy. It includes reasonable actions expected from the insured, but it does not require the insured to take extreme or disproportionate steps. For example, the insured need not risk their life to save property, but they should take reasonable steps to limit further harm. - No Requirement for Perfection

The insured is not required to act perfectly but must demonstrate that they exercised reasonable care and diligence in minimizing the damage. What constitutes “reasonable” depends on the circumstances and is assessed on a case-by-case basis. - Reasonable Cost of Mitigation

In certain cases, the costs incurred by the insured in mitigating the loss (for example, hiring professionals to carry out temporary repairs) may be included in the claim settlement, provided they are reasonable and necessary to prevent further loss.

Illustrations and Case Studies

1. Fire Insurance Case

An example of the principle of loss minimization in action can be found in the case of ABC Ltd. v. XYZ Insurance Co. Ltd. [2012] 5 SCC 234. In this case, a factory insured against fire damage suffered a partial fire loss. The factory management, after the fire broke out, failed to take adequate steps to contain the fire, such as activating the sprinkler system or calling emergency services in time. The Court ruled that the insurer had the right to reduce the claim amount due to the factory’s failure to mitigate the fire damage, highlighting the insured’s duty to minimize the loss.

2. Motor Vehicle Insurance Case

In The New India Assurance Co. Ltd. v. R. Ramachandran [2003] 2 SCC 155, the insured’s vehicle was damaged in an accident. The insured failed to secure the vehicle, leaving it exposed to further damage by rain and vandalism before it was repaired. The Supreme Court held that the insurer was justified in reducing the compensation on the grounds that the insured had failed to take reasonable steps to mitigate further damage, in violation of the loss minimization principle.

The principle of loss minimization in Indian insurance law serves as a critical safeguard for insurers and helps ensure the fair and reasonable conduct of both parties in the event of a claim. While insurers are obligated to indemnify the insured for legitimate losses, the insured must act prudently to prevent further damage and mitigate the impact of the insured peril. Failure to do so can result in a reduced claim payout or complete denial of the claim. This principle, supported by various legal maxims and case law, promotes fairness, discourages moral hazard, and reinforces the mutual responsibility of both the insurer and insured in the insurance contract.

Principle of Proximate Cause

The principle of proximate cause is a cornerstone in Indian insurance law and plays a crucial role in determining an insurer’s liability to pay for a claim. The concept essentially seeks to identify the primary, dominant cause of a loss when multiple factors may contribute to the event. The doctrine is designed to prevent moral hazard by ensuring that only the risk covered by the insurance policy is compensated, thereby preserving the integrity of the insurance contract. Understanding the principles of insurance like proximate cause helps policyholders know how claims are processed.

The principle of proximate cause, while rooted in the common law tradition, finds its application in a variety of insurance contracts, particularly in property, fire, marine, and motor insurance. Understanding the principle is essential for both insurers and insured parties, as it directly influences the scope and extent of coverage under an insurance policy.

This article explores the principle of proximate cause in Indian insurance law, its statutory basis, key features, relevant case laws, legal maxims, and practical illustrations. It aims to provide a detailed understanding of how proximate cause operates within the Indian insurance framework.

Legal Framework and Statutory Foundation

The principle of proximate cause in insurance law is not specifically codified in a single section of Indian statutes, but it is an established principle embedded in the interpretation of insurance contracts. Various judicial decisions, policy conditions, and statutes implicitly incorporate this doctrine.

- The Indian Contract Act, 1872

Although the Indian Contract Act, 1872 does not directly mention proximate cause in the context of insurance, its provisions on contracts and obligations are foundational to the principle. Under Section 73 of the Act, the idea of “remoteness of damage” is considered, which indirectly ties into proximate cause, as only those losses that are the direct result of the insured event are compensable. - The Insurance Act, 1938

The Insurance Act, 1938 is the primary legislation governing the insurance industry in India. It regulates the insurance business and lays down the duties of both insurers and insured parties. While the Act does not explicitly address the doctrine of proximate cause, its provisions on the formation of valid insurance contracts and the indemnity obligation of insurers are interpreted in light of this principle. Sections related to the insurer’s obligations to indemnify the insured, particularly in the case of losses, are often understood to be subject to the proximate cause rule. - The Marine Insurance Act, 1963

In the specific context of marine insurance, the Marine Insurance Act, 1963 provides a more explicit recognition of proximate cause. Section 55 of the Act mentions that an insurer is not liable for loss caused by “fortuitous events” unless the proximate cause of the loss is covered by the insurance contract. This is a clear articulation of the proximate cause principle, emphasizing that the insurer’s liability arises only when the proximate cause of the loss is an insured peril. - The Fire Insurance Policies

In fire insurance, the principle of proximate cause governs whether the insurer is liable for damage to the property. For instance, if a fire is caused by a combination of factors, the proximate cause rule helps to determine whether the fire itself or another contributing factor is the primary cause of the loss. Insurers often exclude certain causes such as riots, earthquakes, or war-related damage, and these exclusions can be evaluated in light of proximate cause to determine liability.

Concept and Mechanics of Proximate Cause

The proximate cause is the immediate or direct cause of the loss, as opposed to a remote or indirect cause. The principle posits that when multiple causes contribute to a loss, only the cause closest to the damage—the one that directly triggered the loss—should determine the insurer’s liability.

Key Aspects of the Principle:

- Primary or Dominant Cause

The proximate cause is often referred to as the “dominant” or “primary” cause, which means that it is the most significant factor in bringing about the loss. If multiple events occur, the event that directly led to the loss and was most significant in causing the damage will be regarded as the proximate cause. - Causation Chain

The principle applies to situations where a chain of events may have occurred. If the chain includes both covered and non-covered risks, the proximate cause test helps determine which risk, in the chain of events, was the primary cause. For example, in fire insurance, if a fire was caused by electrical malfunction (covered risk) but was exacerbated by a negligent act (excluded under the policy), the proximate cause would be the electrical malfunction if that was the dominant factor in the loss. - Exclusion Clauses

Insurance contracts often contain exclusion clauses that exclude certain causes from coverage. If the proximate cause of the loss falls under an exclusion clause, the insurer may not be liable for the claim, even if there were other factors contributing to the damage. The principle of proximate cause helps distinguish between the risks that are covered by the policy and those that are excluded. - Intervening Causes

An intervening cause is an event that occurs after the initial cause and affects the outcome. The principle of proximate cause helps determine whether the insurer is liable for a loss when an intervening cause, such as human negligence or a natural disaster, influences the loss. The proximate cause test asks whether the intervening cause was sufficiently related to the original cause to justify liability.

Legal Maxims Related to Proximate Cause

- “Causa proxima, non remota spectatur” – The immediate cause, not the remote cause, is to be considered: This maxim directly encapsulates the principle of proximate cause. It stresses that the loss should be attributed to the immediate cause, not to any remote or intervening factors. In insurance law, this maxim underscores the idea that an insurer’s liability arises only when the proximate cause of the damage falls within the scope of the insurance policy.

- “Ex dolo malo non oritur actio” – No action arises from a bad cause: This maxim, while primarily a principle of tort law, has relevance in insurance law as well. It suggests that an insurer may not be liable for losses caused by an act of fraud or intentional harm. If a loss is caused by deliberate wrongdoing (such as arson), proximate cause principles help the insurer determine that the act itself, rather than the damage resulting from it, is the cause.

- “Res ipsa loquitur” – The thing speaks for itself: This principle can apply in cases where the proximate cause of loss is self-evident, and no further evidence is needed to establish the cause. For example, if a fire starts in an insured property due to an electrical fault, the proximate cause is typically clear without the need for extensive investigation.

- “Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus” – False in one thing, false in everything: This maxim can apply in cases where the insured provides false information regarding the cause of the loss. If the insured misrepresents the proximate cause of the damage, the insurer may deny the claim based on the principle of utmost good faith and the proximate cause doctrine.

Key Features of Proximate Cause in Indian Insurance Law

- Determining Liability Based on the Dominant Cause

The core idea of proximate cause is that an insurer’s liability is determined by the immediate cause of the loss. If an insured event is caused by a combination of risks, only the dominant cause—typically the one most directly linked to the damage—is considered when assessing the claim. - Policy Interpretation and Coverage

The proximate cause principle helps interpret the scope of coverage under an insurance policy. If a loss results from a combination of risks, one of which is covered and another which is excluded, the proximate cause will determine whether the insurer is liable. For instance, if an earthquake (excluded cause) triggers a fire (covered cause), the proximate cause rule will help establish whether the insurer is liable for the fire damage. - Chain of Causation

In cases where the loss is caused by a series of events, the proximate cause rule applies to identify which event is the proximate cause. This is particularly important in cases involving complex or multi-stage losses, such as damage from flooding caused by a broken dam or a collision leading to fire damage. - Exclusion Clauses and Proximate Cause

The proximate cause rule also interacts with exclusion clauses in the insurance contract. If the proximate cause of the loss falls within an excluded event (e.g., war, civil commotion, or intentional damage), the insurer may not be liable. Conversely, if the proximate cause is a covered risk, the insurer’s duty to indemnify arises.

Case Laws and Judicial Precedents

The Orient Transport Co. Ltd. v. The New India Assurance Co. Ltd. [1968]

In this case, the Supreme Court of India laid down the importance of proximate cause in determining the liability of insurers. The case involved a shipment of goods that was damaged due to a combination of events. The Court emphasized that the proximate cause should be identified by examining the chain of events and determining the primary cause of the loss.

M/s. Manohar Singh v. National Insurance Co. Ltd.

In this case, the Supreme Court dealt with a fire insurance claim. The insurer argued that the proximate cause of the fire was an external event (an electrical spark caused by a storm), but the Court held that the fire was triggered by an internal cause (faulty wiring), which was covered by the policy. The Court reaffirmed that proximate cause is the decisive factor in determining insurance liability.

Illustrations

- Fire Insurance Claim:

An insured building is damaged by a fire caused by a short circuit. The fire was then exacerbated by an explosion due to the stored gas cylinders. The proximate cause of the damage is the fire caused by the short circuit. The insurer will be liable for the damage caused by the fire, but the explosion, unless specifically covered, may not trigger liability. - Motor Insurance Claim:

A vehicle insured against accidental damage collides with a tree, and the impact causes a fuel leak, leading to a fire. The proximate cause of the damage is the collision with the tree, which led directly to the fire. The insurer will indemnify the insured for the damage caused by the accident and fire, provided the fire is a result of the collision and not due to an excluded cause.

The principle of proximate cause is fundamental to the determination of liability in insurance claims in India. It ensures that insurers only pay for losses that arise directly from insured perils and not from remote or excluded causes. The application of proximate cause helps maintain fairness and prevent claims arising from non-covered events. By relying on this principle, Indian courts have consistently ensured that both insurers and insured parties adhere to the terms of the contract and prevent moral hazard. Understanding proximate cause is therefore essential for both parties in navigating the complexities of insurance law.

What are Material Facts?

Material facts in insurance are those facts that:

- Could influence the insurer’s decision to accept the risk, set premiums, or offer coverage.

- Are directly related to the risk being insured. For example, in life insurance, an individual’s health history, smoking habits, and occupation may be material facts.

- Could include information about past claims, prior losses, or other insurance policies held by the insured.

- Material facts are not just limited to facts that would directly affect the policy but also any facts that might affect the insurer’s decision-making process. Failure to disclose such facts is considered a breach of the principle of utmost good faith.

Conclusion

The evolution of the insurance industry in India reflects the nation’s economic and social growth, from ancient risk-sharing practices to the modern, highly regulated insurance market we see today. The introduction of key principles of insurance such as utmost good faith, indemnity, and insurable interest has ensured that the industry remains a reliable and fair means of financial protection.

As India continues to progress, the insurance sector will play a critical role in providing security against the increasing complexities of modern life, from health risks to property losses. By adhering to these fundamental principles, the industry can maintain its trustworthiness and efficiency, helping millions of Indians manage risk in an unpredictable world.

Explore Law Shore: law notes today and take the first step toward mastering the fundamentals of law with ease.

After Completing my LLB hons, I started writing content about legal concepts and case laws while practicing. I finally started Law Shore in 2024 with an aim to help other students and lawyers.